The conversation you’ve rehearsed a thousand times in your head finally happens at the kitchen table. Your mother’s defensive walls go up the moment you mention childhood memories. Your father changes the subject when emotions surface. The patterns feel as familiar as they are frustrating. You’re trying to heal, to break cycles that have persisted through generations, but the very people you need to talk with seem incapable of hearing you.

This struggle reflects a profound challenge facing millions of adults today. Research from the American Psychological Association indicates that unresolved family trauma affects up to 61% of adults, with many reporting that attempts to address these issues with parents feel impossible or retraumatizing. The gap between generations, shaped by different cultural contexts, emotional languages, and survival mechanisms, can feel insurmountable.

Yet within this challenge lies transformative potential. Studies on intergenerational trauma transmission show that even one family member’s healing journey can disrupt patterns that have persisted for decades. When adult children learn to navigate these conversations skillfully, they not only heal their wounds but also create possibilities for entire family systems to evolve. The journey requires understanding both your parents’ limitations and your power to change generational patterns, regardless of their participation.

Understanding Your Parents’ Communication Patterns

Every generation develops its emotional vocabulary within specific historical and cultural contexts. Your parents’ communication patterns likely emerged from their own childhood experiences, societal expectations, and survival needs. Research published in the Journal of Marriage and Family reveals that parental communication styles are significantly influenced by the socioeconomic and cultural conditions of their formative years.

Many parents from older generations grew up in environments where emotional expression was viewed as a sign of weakness or self-indulgence. The “strong and silent” archetype dominated masculine ideals, while women often learned to suppress their needs in the service of family harmony. These patterns weren’t character flaws; they were adaptive strategies for their time and circumstances.

Understanding the historical context of your parents’ emotional development provides a crucial perspective. Parents who lived through economic hardship, war, immigration, or social upheaval often developed hypervigilance and emotional suppression as protective mechanisms. Trauma researchers have documented how survival-mode functioning can become entrenched across generations, with parents unconsciously passing down coping mechanisms that no longer serve their children.

Common communication patterns in trauma-affected families include:

Deflection and Minimization: When confronted with emotional topics, many parents reflexively minimize experiences (“It wasn’t that bad”) or deflect to comparisons (“You had it better than I did”). This isn’t necessarily gaslighting; it’s often a protective mechanism against their unprocessed pain.

Emotional Flooding or Shutdown: Some parents become overwhelmed when emotional topics arise, either exploding in defensive anger or completely withdrawing. Neurobiological research shows that trauma can dysregulate the nervous system, making emotional conversations feel genuinely threatening to the body.

Role Reversal: In families affected by trauma, children often become emotional caretakers for their parents. Adult children may find their parents expecting them to continue this role, making it difficult to express their own needs or experiences.

Cultural Binding: Parents may invoke cultural or religious traditions to shut down conversations: “In our culture, we don’t talk about these things” or “Honor thy father and mother.” While culture provides important context, it can also be weaponized to avoid accountability.

Recognizing Trauma Responses in Family Dynamics

Before attempting healing conversations, it’s essential to recognize how trauma manifests in family communication. Dr. Bessel van der Kolk’s groundbreaking research demonstrates that trauma lives in the body, affecting how people perceive and respond to emotional stimuli long after the original threat has passed.

Your parents’ defensive responses to emotional conversations may include:

Somatic Responses: Watch for physical signs of distress: rapid breathing, flushed face, rigid posture, or sudden fatigue. These bodily responses indicate their nervous system is activated, making productive conversation unlikely.

Cognitive Patterns: Trauma can create rigid thinking patterns. Parents might exhibit black-and-white thinking (“I was either a perfect parent or a complete failure”), catastrophizing (“If I admit any mistakes, our whole relationship will fall apart”), or persistent denial of documented events.

Behavioral Patterns: Notice if conversations consistently follow predictable scripts. Does your mother always become ill when difficult topics arise? Does your father suddenly remember urgent tasks? These patterns reveal how the family system organizes itself to avoid perceived threats.

Understanding these responses helps you approach conversations with appropriate expectations and strategies. It’s not about excusing harmful behavior but rather understanding its origins to navigate more effectively.

Addressing Childhood Wounds as an Adult

The journey of addressing childhood wounds with parents requires careful preparation and realistic expectations.

Internal Preparation: Before initiating conversations, clarify your intentions. Are you seeking acknowledgment, apology, behavior change, or simply the opportunity to be heard? Research on family reconciliation shows that unclear objectives often lead to retraumatization rather than healing.

Write letters you’ll never send to process raw emotions. Work with a therapist to identify your triggers and develop self-soothing strategies. Practice conversations with trusted friends who can role-play your parents’ likely responses. This preparation isn’t about scripting perfection; it’s about building internal resources.

Choosing Your Battles: Not every childhood wound requires confrontation. Consider which issues genuinely need addressing for your healing versus those you can process independently. Studies on trauma recovery indicate that empowerment comes from choosing when and how to engage, rather than feeling compelled to address everything.

Starting Small: Begin with less charged topics to test your parents’ capacity for emotional conversation. If they can’t acknowledge that forgetting your tenth birthday was hurtful, they’re unlikely to process larger traumas. These small conversations serve as diagnostic tools for what’s possible.

Using “I” Statements Effectively: While “I” statements are common advice, they require nuance in trauma conversations. Instead of “I feel hurt when you dismiss my experiences,” try “I’m working to understand my childhood experiences and would value your perspective on some memories I have.” This approach invites collaboration rather than triggering defensiveness.

Timing and Setting: Creating Optimal Conditions

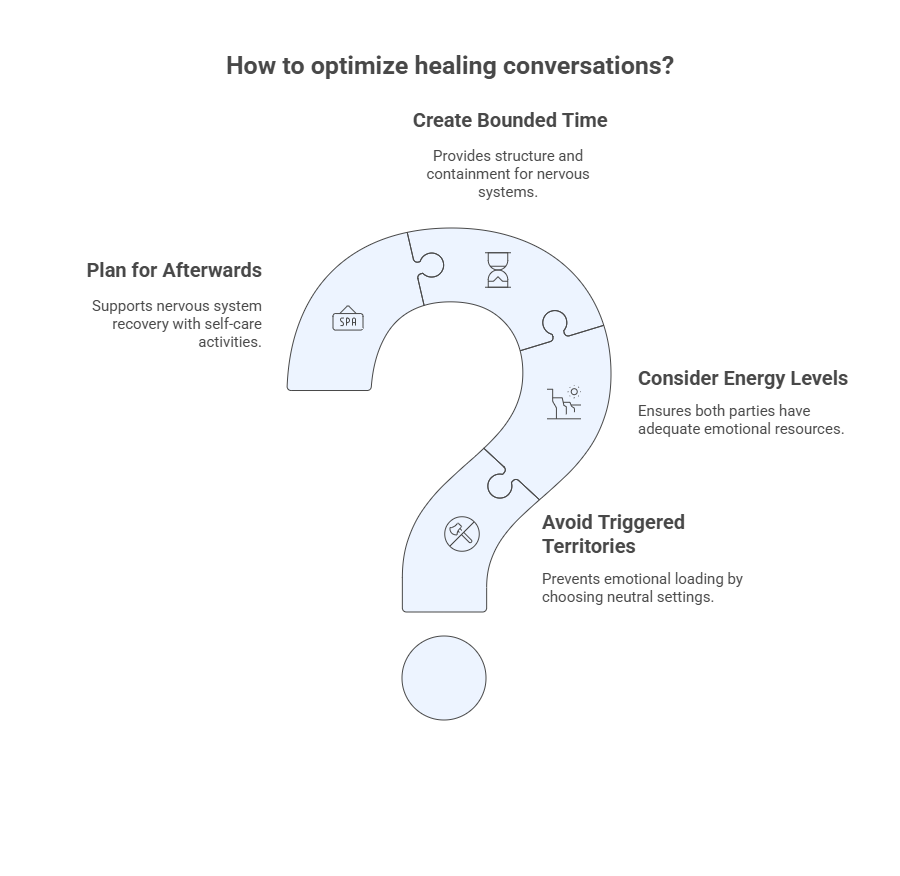

The when and where of healing conversations significantly impact their success. Environmental psychology research demonstrates that physical settings profoundly influence emotional regulation and communication patterns.

Avoiding Triggered Territories: Holiday gatherings, childhood homes, or anniversary dates of traumatic events create emotional loading that sabotages conversations. Choose neutral times and spaces where family dynamics are less activated.

Considering Energy Levels: Both you and your parents need adequate emotional resources for difficult conversations. Avoid times of stress, illness, or major life transitions. Morning conversations often work better than evening ones when defenses are higher and energy is lower.

Creating Bounded Time: Open-ended conversations can become overwhelming. Consider setting gentle time boundaries: “I’d like to talk with you about something important for about an hour this Saturday. Would morning or afternoon work better?” This structure provides containment for everyone’s nervous system.

Planning for Afterwards: Have self-care plans for immediately after conversations. Arrange calls with supportive friends, schedule therapeutic activities, or plan gentle movement. Your nervous system will need support regardless of how the conversation goes.

Setting Boundaries Without Destroying Relationships

Boundary-setting in families affected by generational trauma requires delicate navigation. Research on family systems shows that boundaries often feel like betrayal in enmeshed families, yet they’re essential for healthy relationships.

Differentiating Boundaries from Walls: Boundaries say, “This is where I end and you begin,” while walls say, “I’m shutting you out entirely.” Help parents understand that boundaries preserve relationships by preventing resentment and burnout.

Starting with Behavioral Boundaries: Before addressing emotional boundaries, establish behavioral ones. “I need conversations to happen without yelling” is clearer and more achievable than “I need you to respect my feelings.” Concrete boundaries provide structure for learning new patterns.

The Broken Record Technique: When parents test boundaries, calmly repeat your boundary without justification or argument. “As I mentioned, I’m not comfortable discussing my weight. How’s your garden doing?” Consistency teaches that boundaries are non-negotiable while maintaining connection.

Boundary Gradient: Develop a spectrum of responses based on boundary violations:

- – First violation: Gentle reminder and redirect

- – Second violation: Firm restatement and topic change

- – Third violation: End the conversation with plans to reconnect later

- – Repeated violations: Longer breaks between contacts

Positive Reinforcement: When parents respect boundaries, acknowledge it: “I really appreciated how you heard me when I said I needed to change the subject. It makes me feel closer to you.” This reinforces new patterns through connection rather than punishment.

Cultural Considerations in Family Conversations

Cultural context profoundly shapes how families process emotion and conflict. Cross-cultural psychology research reveals that concepts like individual autonomy, emotional expression, and family hierarchy vary dramatically across cultures.

Collectivist vs. Individualist Tensions: In collectivist cultures, addressing personal wounds may be seen as selfish or disloyal to family harmony. Frame healing conversations in terms of strengthening family bonds: “I want to understand our family better so I can pass on the best of our traditions.”

Language and Emotional Expression: Many languages lack direct translations for therapy concepts like “boundaries” or “emotional validation.” Bilingual family therapy research shows that some emotions can only be accessed in one’s native language, while others emerge more easily in a second language. Consider which language allows for the most authentic expression.

Generational Immigration Trauma: Families with immigration histories carry additional layers of loss, adaptation, and survival stress. Parents who sacrificed for children’s opportunities may feel betrayed by conversations about childhood wounds. Acknowledge their sacrifices while maintaining your truth: “I’m grateful for everything you did to give me opportunities. I’m also working to understand how the stress of those times affected our family.”

Religious and Spiritual Frameworks: Many cultures interweave religious beliefs with family dynamics. Parents might invoke religious concepts to deflect accountability: “Only God can judge” or “We must forgive and forget.” Work within these frameworks when possible: “My faith calls me to truth-telling and healing. I believe addressing these wounds honors our spiritual values.”

Navigating Defensive Responses

When you initiate healing conversations, defensive responses are almost inevitable. Psychological research on defense mechanisms shows they serve protective functions, shielding people from overwhelming emotions or perceived threats to identity.

Common Defensive Patterns:

Denial: “That never happened” or “You’re remembering it wrong”

- Response: “I understand we may remember things differently. This is how I experienced it, and that experience shaped me.”

Minimization: “It wasn’t that bad” or “You’re too sensitive”

- Response: “Impact matters more than intention. Regardless of how it seemed to you, this is how it affected me.”

Deflection: “Well, what about when you…” or “Your sibling never complains”

- Response: “I’m happy to discuss other concerns separately. Right now, I’m hoping we can focus on this specific issue.”

Victimization: “I guess I was just a terrible parent,” or “Nothing I did was ever good enough.”

- Response: “This isn’t about you being bad or good. It’s about understanding experiences that affected me so we can have a better relationship now.”

The STOP Technique: When conversations become too heated:

- – Stop talking and breathe

- – Take a physical step back

- – Observe what’s happening in your body

- – Proceed with a new approach or pause the conversation

When to Accept Limitations vs Push for Change

Discerning when to accept your parents’ limitations versus continuing to push for change requires ongoing assessment. Research on family therapy outcomes indicates that sustainable change requires both capacity and willingness from all parties involved.

Signs of Capacity for Change:

- – Small acknowledgments of impact, even if defensively framed

- – Questions about your experience, even if awkwardly expressed

- – Attempts at different behaviors, however imperfect

- – Emotional responses that indicate the conversation is landing

- – References to the conversation in later interactions

Signs of Fixed Limitations:

- – Consistent denial of documented events

- – Escalating aggression or manipulation in response to boundaries

- – Complete emotional shutdown or dissociation

- – Active attempts to recruit other family members against you

- – Behaviors that jeopardize your safety or mental health

The Graduated Approach: Start with minimal expectations and gradually increase based on demonstrated capacity:

- – Basic acknowledgment that conversations happened

- – Recognition that you experienced pain (without admitting fault)

- – Curious about your experience

- – Acknowledgment of their role

- – Genuine apology and behavior change

If parents consistently cannot move past level one or two, acceptance of limitations may be necessary for your healing.

Creating New Communication Patterns

Regardless of your parents’ participation, you can initiate new communication patterns that disrupt generational cycles. Family systems theory demonstrates that when one member changes their dance steps, the entire system must adjust.

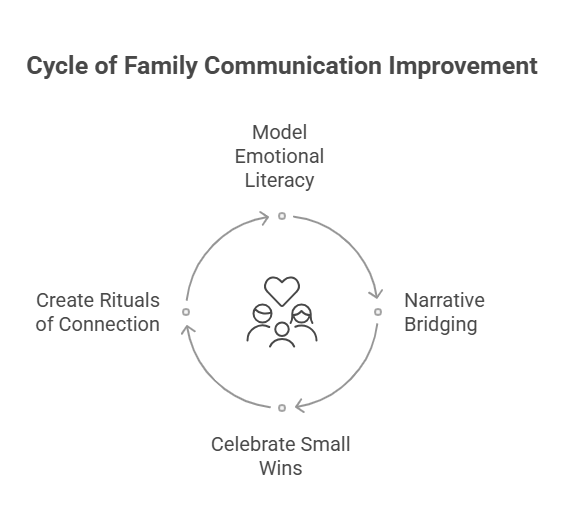

Modeling Emotional Literacy: Use feeling words accurately and specifically. Instead of “fine” or “upset,” try “disappointed,” “hopeful,” “conflicted,” or “grateful.” This expands the family’s emotional vocabulary through demonstration.

Narrative Bridging: Connect current behaviors to understandable origins: “I imagine it’s hard to hear about my childhood pain when you were doing your best with what you knew. And you were dealing with your own father’s anger, which must have been so difficult.” This acknowledges their experience while maintaining your truth.

Celebrating Small Wins: When parents make any movement toward emotional availability, acknowledge it enthusiastically: “Dad, when you asked how therapy was going, that meant so much to me. I felt seen by you.” This reinforces new behaviors through positive connections.

Creating Rituals of Connection: Establish new traditions that foster emotional safety. Weekly phone calls with agreed-upon topics, monthly letters sharing gratitudes, or annual trips focused on creating new memories can slowly shift family dynamics.

Working with Intergenerational Patterns

Understanding how trauma patterns transmit across generations empowers more effective intervention. Epigenetic research reveals that trauma can alter gene expression in ways that pass to subsequent generations, but also that healing interventions can modify these expressions.

Mapping Family Patterns: Create a genogram or family tree that tracks emotional patterns, coping mechanisms, and traumas across generations. Notice how your grandmother’s loss became your mother’s anxiety, which became your hypervigilance. Understanding these connections reduces personal blame and increases compassion.

Identifying Pattern Breaks: Celebrate where patterns have already shifted. Maybe your parents didn’t hit you despite being hit themselves. Perhaps they provided education they never received. Acknowledging existing progress creates the foundation for further change.

Future-Focused Healing: Frame conversations around breaking cycles for future generations: “I’m working on this so my children won’t have to.” This shared investment in family legacy can motivate parents who struggle with personal accountability.

The Role of Professional Support

Navigating generational trauma often requires professional guidance. Research indicates that family-of-origin work is most effective when supported by trained therapists who understand intergenerational dynamics.

Individual Therapy: Work with a therapist experienced in family systems and trauma to:

- – Process childhood experiences safely

- – Develop communication strategies

- – Practice conversations through role-play

- – Build internal resources for difficult interactions

- – Integrate experiences regardless of parental participation

Family Therapy Considerations: If parents are willing, family therapy can provide a structured space for healing conversations. However, ensure the therapist understands trauma dynamics and won’t inadvertently enable harmful patterns. Interview potential therapists about their approach to power dynamics and accountability in families.

Support Groups: Adult children of traumatized parents benefit from witnessing others’ journeys. Groups provide validation, strategy-sharing, and hope through seeing various stages of healing. Online communities can offer support when local resources are limited.

AI-Enhanced Support: Modern AI platforms can provide 24/7 support for processing difficult conversations, practicing responses, and tracking patterns over time. These tools offer judgment-free spaces to explore emotions and develop strategies between therapy sessions.

Long-Term Healing and Integration

Healing generational trauma is not a destination but an ongoing journey of integration and growth. Longitudinal studies on trauma recovery show that healing happens in spirals rather than straight lines, with each cycle bringing deeper integration.

Grieving Multiple Losses: Acknowledge that healing involves grieving:

- – The childhood you needed but didn’t receive

- – The parents you wished for but didn’t have

- – The relationship you hoped for but may never achieve

- – The time lost to dysfunction and pain

Creating Chosen Family: Build relationships that provide what biological family cannot. These connections offer templates for healthy dynamics and support your ongoing growth. Chosen family can include friends, mentors, spiritual communities, or therapeutic relationships.

Becoming the Parent to Yourself: Develop internal nurturing voices to counteract critical or neglectful parental introjects. This involves actively providing yourself with validation, comfort, encouragement, and boundaries that your parents couldn’t offer.

Living Your Values: Define and embody values that may differ from family traditions. This differentiation allows you to honor your heritage while creating new patterns aligned with your authentic self.

Measuring Progress and Success

Success in breaking generational trauma looks different for each person and family. Trauma recovery research emphasizes that healing is marked by increased flexibility, choice, and resilience rather than the absence of all triggers or perfect relationships.

Internal Markers of Progress:

- – Decreased emotional reactivity to parents’ behaviors

- – Ability to stay grounded during difficult conversations

- – Reduced rumination or obsession about family dynamics

- – Increased capacity for self-compassion

- – Freedom to choose when and how to engage

Relational Markers of Progress:

- – More authentic interactions, even if limited

- – Ability to enjoy parents’ positive qualities despite limitations

- – Decreased need for parental validation or approval

- – Capacity to set and maintain boundaries calmly

- – Freedom from repetitive conflict cycles

Generational Markers of Progress:

- – Different patterns with your children or mentees

- – Ability to discuss family history without shame

- – Integration of cultural strengths while releasing harmful patterns

- – Modeling healthy conflict resolution

- – Creating new family narratives and traditions

Moving Forward with Compassion

Breaking generational trauma through healing conversations with parents requires immense courage, patience, and self-compassion. The journey involves holding multiple truths simultaneously: your parents were likely doing their best with their wounds, and their best may have caused you significant harm. Both realities deserve acknowledgment.

Remember that healing happens on multiple levels. Even if your parents never acknowledge their role or change their behavior, your willingness to address these patterns transforms the generational trajectory. Every conscious choice to respond differently, every boundary lovingly held, every moment of self-compassion instead of self-criticism rewrites your family’s future.

The ultimate goal isn’t to achieve perfect resolution or movie-scene reconciliations. It’s to free yourself from unconscious repetition of harmful patterns, to choose your responses rather than react from programming, and to create space for whatever authentic relationship is possible with the parents you have.

Your healing matters, not just for you but for everyone whose life you touch. By breaking these cycles, you offer gifts to past generations who couldn’t heal, present relationships that benefit from your growth, and future generations who will inherit healthier patterns. This is sacred work, worthy of all the effort, tears, and transformation it requires.

Ready to navigate your journey of breaking generational trauma? Theryo’s AI-enhanced platform provides personalized support for processing family dynamics, preparing for difficult conversations, and tracking your healing progress. Transform your family’s future by healing your past. Start your supported journey today.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What if my parents refuse to have any emotional conversations?

Focus on your healing through individual therapy, journaling, and support groups. You can break generational patterns through your work, even without parental participation. Consider writing letters you don’t send, having imaginary conversations, or working with a therapist on empty chair exercises. Your healing doesn’t depend on their involvement.

Q: How do I handle siblings who want to maintain family denial?

Respect that each family member has their own healing timeline and coping mechanisms. Share your journey without pressuring them to join. Set boundaries around family loyalty demands: “I support your choice to relate to Mom differently. I need you to respect my choices, too.” Find support outside the family system to avoid isolation.

Q: Is it worth trying if my parents are elderly or have health issues?

Consider what you need for your peace. Sometimes a simple acknowledgment or one honest conversation provides closure. Adjust expectations based on their capacity. Focus on what you need to say rather than what you need them to understand. Many people find writing letters (sent or unsent) helps process feelings when direct conversation isn’t possible.

Q: What if addressing trauma makes things worse initially?

Temporary escalation often occurs when disrupting long-standing patterns. Your parents’ increased defensiveness might indicate the conversation is touching something real. Ensure you have adequate support during this phase. If safety becomes a concern, prioritize protection over reconciliation. Consider taking breaks to let everyone integrate before continuing.

Q: How do I know if I should go no-contact with parents?

No-contact is a valid choice when relationships threaten your safety, sanity, or sobriety. Consider it if parents consistently violate major boundaries, engage in abuse, or trigger mental health crises. This decision often benefits from professional support. Remember that no-contact can be temporary or permanent, partial or complete, based on your needs.

Q: Can healing happen if parents have mental illness or addiction?

Mental illness and addiction complicate but don’t prevent healing work. Adjust expectations based on their capacity. Focus on understanding how their struggles affected you rather than expecting accountability they can’t provide. Al-Anon and similar programs offer specific support for family members dealing with addiction.

Q: What if my parents use culture or religion to avoid accountability?

Research how healthy families within your culture/religion handle conflict and accountability. Find cultural or religious leaders who understand trauma to provide alternative perspectives. Frame your healing in cultural values: “Our culture values family strength. Addressing these wounds makes our family stronger.” You can honor heritage while rejecting harmful patterns.

Q: How do I handle parents who weaponize therapy language?

Parents who use psychological concepts to avoid accountability (“You’re projecting” or “That’s your trigger to work on”) require careful navigation. Don’t engage in psychological debates. Return to simple truths: “Regardless of the psychological interpretation, this behavior hurts me and needs to stop.” Focus on behaviors rather than analyses.

Q: Should I involve other family members as mediators?

Be cautious about triangulation. Well-meaning relatives often lack the skills to navigate trauma dynamics and may inadvertently enable harmful patterns. If you involve others, choose those who understand trauma and can maintain neutrality. Professional mediators or family therapists provide more effective support than relatives.

Q: What if I can’t remember childhood clearly but know something was wrong?

Trust your body’s wisdom and emotional responses. Trauma often disrupts memory formation. Focus on present-day patterns and how family dynamics currently affect you rather than requiring specific memories. Work with trauma-informed therapists who understand implicit memory and somatic experiences.

Q: How long should I try before accepting limitations?

There’s no universal timeline. Some suggest trying for one year with consistent boundaries and clear communication. Others recommend three significant attempts. Trust your intuition and energy levels. When the effort to create change consistently outweighs any progress, it may be time to shift focus to acceptance and self-protection.

Q: Can relationships improve after periods of no contact?

Yes, many families report improved dynamics after boundaries create space for growth. No contact can provide time for everyone to process, seek help, or gain perspective. If you resume contact, start slowly with clear boundaries. Some relationships need distance to find their sustainable level of connection.

Q: How do I explain this work to partners or friends who have healthy families?

Use concrete examples rather than abstract concepts. Share specific behaviors and their impacts rather than psychological analyses. Ask for support rather than advice. Consider sharing resources about family trauma to help them understand. Remember that their inability to fully grasp your experience doesn’t invalidate it.

Q: What if addressing trauma conflicts with being a “good” son/daughter?

Redefine what being a good adult child means. Sometimes the most loving act is refusing to enable dysfunction. Breaking generational trauma serves your entire family line, even if current members can’t see it. Being “good” includes being true to yourself and creating healthier patterns for future generations.

Q: Is it possible to have a relationship while still healing from childhood wounds?

Absolutely. Many people maintain limited but meaningful relationships with parents while continuing their healing journey. This requires clear boundaries, realistic expectations, and separate spaces for processing wounds. Focus on present-day interactions while doing deeper healing work in therapy or support groups.